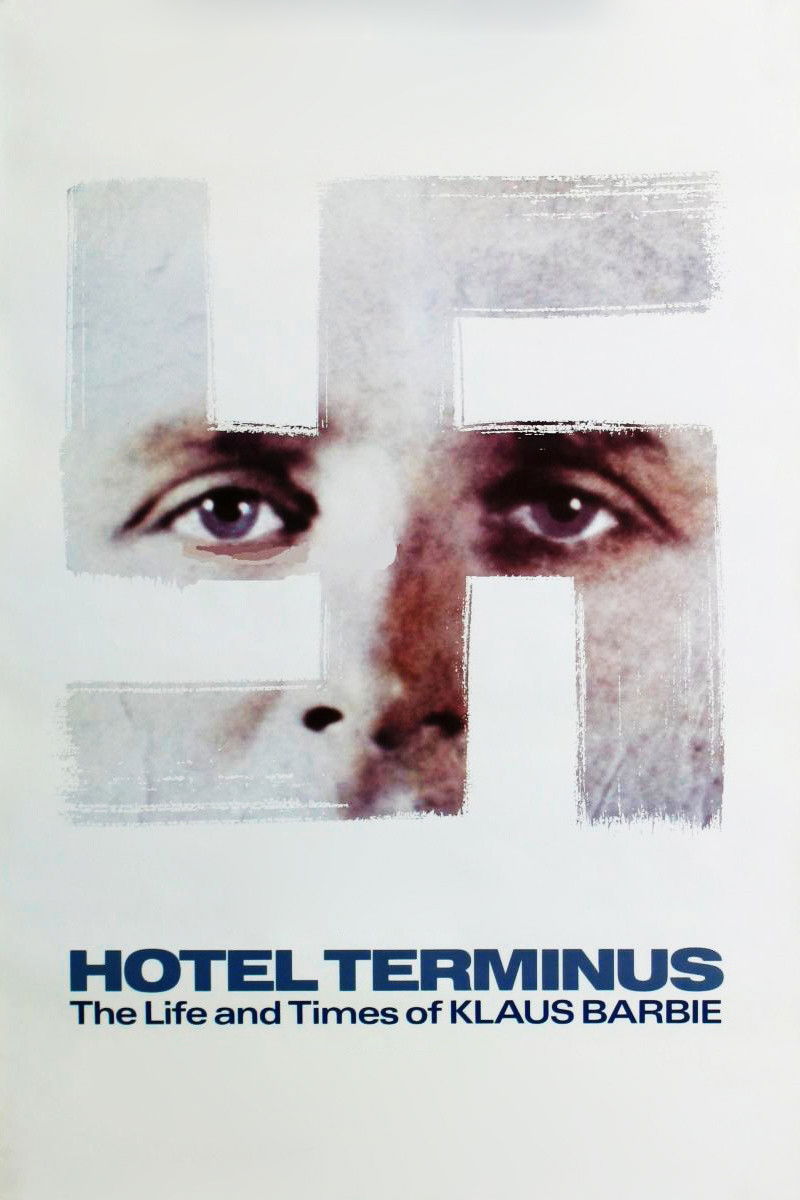

Marcel Ophuls' riveting film details the heinous legacy of the Gestapo head dubbed "The Butcher of Lyon." Responsible for over 4,000 deaths in occupied France during World War II, Barbie would escape—with U.S. help—to South America in 1951, where he lived until a global manhunt led to his 1983 arrest and subsequent trial.

18 years after his last film, (The Troubles We've Seen), Marcel Ophuls emerges from retirement as one of our last masters, the most corrosive, the funniest as well. And the most forceful. The director of The Sorrow and the Pity shares with us stories of his exceptionally rich life in this light-hearted yet bitter escapade though the century and the movies. Son of the great Max Ophuls, he is generous in his admiration. We also meet Jeanne Moreau, Bertolt Brecht, Ernst Lubitsch, Otto Preminger, Woody Allen, Stanley Kubrick and of course François Truffaut. There are no great filmmakers without a memory, so here is the memory shop of Marcel Ophuls.

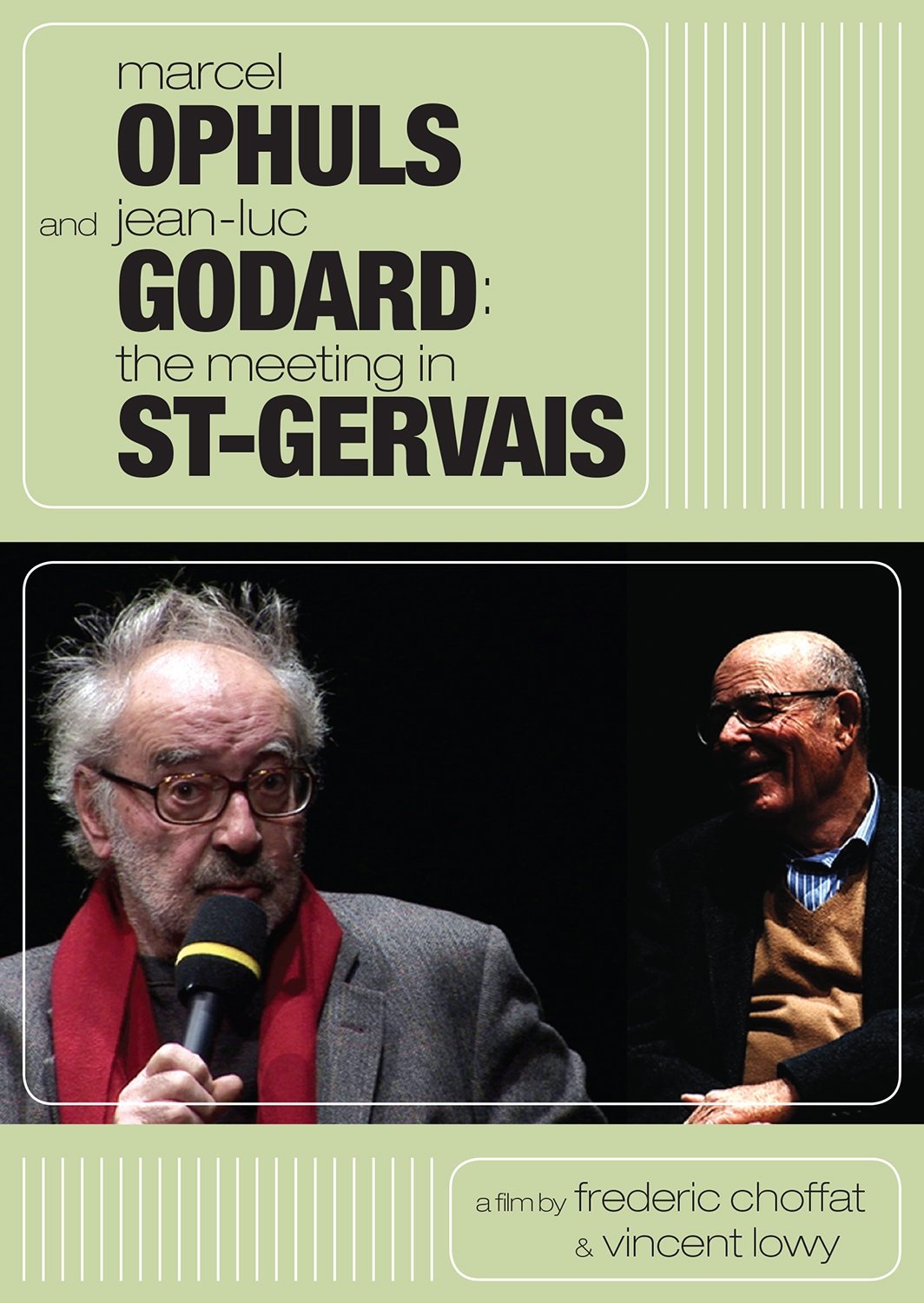

In 2009, in a small theater in Geneva, Switzerland, the film directors Marcel Ophuls and Jean-Luc Godard met for an unusual, surprisngly intimate and sometimes contentious dialogue with each other in front of a live audience. Luckily for us, it was filmed.

Storyville's Nick Fraser meets German-French documentary film maker and former actor, Marcel Ophüls.

Television film

Liberty Belle tells the story of a group of student's involvement with a group who oppose the French Algerian war. The film premiered at the 1983 Cannes Film Festival.

The process of making Shoah.

Philippe Roger found the secretary of director Max Ophüls, Ulla de Colstoun, and Valere his first assistant, mobilized them on his project and, together during the documentary, they will both find in Normandy, the filming locations of Maison Tellier, sketch of the film Le Plaisir and the spirit of the film with the still intact impressions of these exceptional witnesses.

A 1965 episode of the French television program Cinéastes de notre temps, featuring interviews with many of film director Max Ophuls’s collaborators

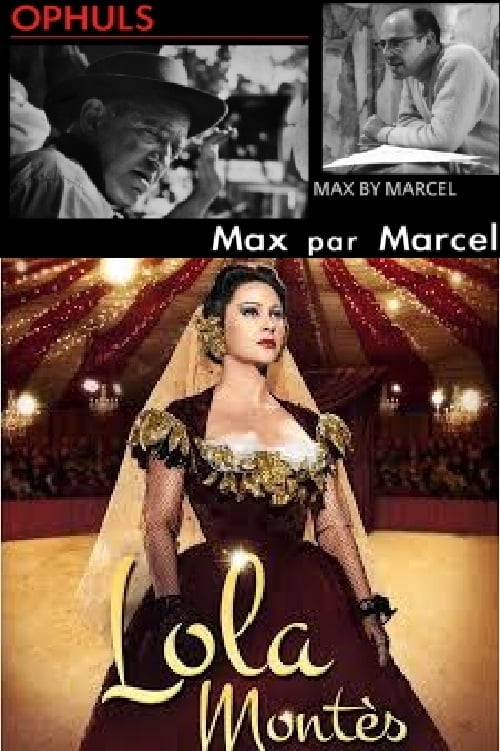

In a series of four documentaries, Marcel Ophuls pays tribute to his father Max, and in this last one discusses his role as an assistant director on "Lola Montès".

An interview with French documentarian Marcel Ophüls about his father Max Ophüls, regarding Max's arrival in Hollywood, how he received approval for Letter from an Unknown Woman (1948) from the head of the studio, his return to France, and what Marcel has learned from his father. An extra on Olive Signature's Blu-Ray release of Letter from an Unknown Woman.

Twenty-six people - including two daughters, an ex-wife, his last lover, actors, fellow directors and writers, a neighbor, and boyhood friends - talk about François Truffaut. They discuss his attitudes toward wealth, his early writings about cinema, the undercurrent of violence in his films and his personality, the way he used and altered events in his life when making films, his search for a father (both artistic and biological), his relationship with his mother, the scenes in his films that cause a squirm of embarrassment, and his ultimate mysticism. Clips from a dozen of his films are included.

Marcel Ophüls interviews various important Eastern European figures for their thoughts on the reunification of Germany and the fall of Communism.

In 1912, in Austria, the painter Egon Schiele is sent to jail accused of pornography with the nymphet Tatjana in his erotic paints. His mate, the model Vally, gets help from a famous lawyer to release him. Then he leaves Vally, marries with another woman and goes to the war.

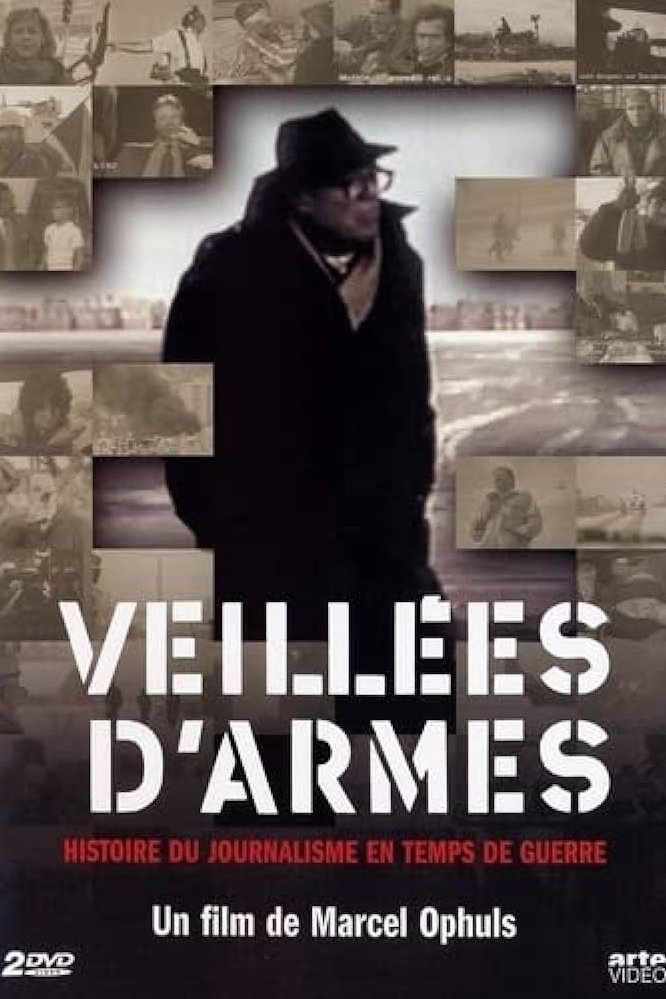

We follow Marcel Ophuls' two journeys to Sarajevo in 1993. He is starting a documentary about war correspondants. But this also becomes a reflexion about truth and life. The form consists in many interviews of mostly French and American journalists and reporters of television or newspapers.

The story of the documentary The Sorrow and the Pity (1971), directed by Marcel Ophüls, which caused a scandal in a France still traumatized by the German occupation during World War II, because it shattered the myth, cultivated by the followers of President Charles de Gaulle (1890-1970), of a united France that had supposedly stood firm in the face of the ruthless invaders.